I was reminded this week of the paradox of the Ship of Theseus, which asks: Is an object the same if you’ve rebuilt the entire thing, one piece at a time?

This thought experiment takes its name from the story of Theseus, the legendary ancient king of Athens. Theseus was most famous for his defeat of the Minotaur, the half-human, the-bull monster to whom the Athenians were compelled to send young nobles to be sacrificed every few years. Theseus escaped the Labyrinth, rescued the victims, and sailed back to safety in Athens. And every year afterwards, the people of Athens celebrated this great day, by taking the ship on a sailing pilgrimage to Athens to honor Apollo.

Of course, keeping the ship seaworthy for generations meant frequent repairs, and eventually philosophers began to ask questions. Replacing a single part clearly doesn’t make it a different boat. But after centuries of maintenance, if each individual board and plank, each mast and sail, had been replaced since Theseus’s day—Could we really say that it’s still “The Ship of Theseus” at all?

It’s a decent question to ask of the church, as well.

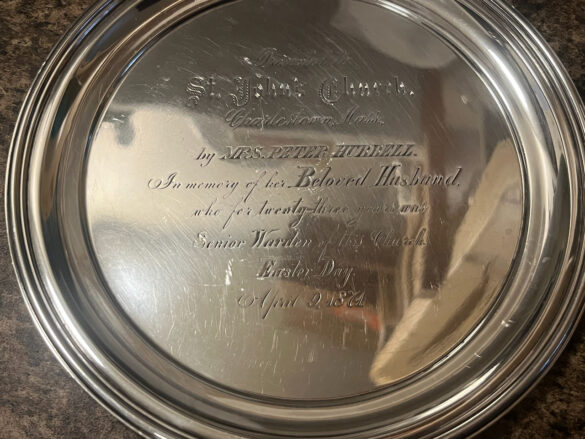

I don’t think that this is only because as I write these words, I’m watching workers from Lyn Hovey’s stained glass studio scale the scaffolding outside my office to replace the stained-glass window in the nave, now beautifully restored. I don’t think it’s only because the kitchen is being upgraded and the paths in the Garden have been paved. The list of constant maintenance goes on—I can name the bell, and the door, and the organ, and more. The church is not the building, and the building is not the church, and yet in some real sense it is the ship in which we sail. (That’s why we call the body of the church the “nave”— navis is just Latin for a ship!) The building is a place of beauty in which we gather to worship God and spend time with one another, and if the work of rebuilding it piece by piece never seems to end, it’s sometimes helpful to remember that the only alternative is a ship that’s full of leaks.

But the church itself is constantly rebuilt, as well. And now I mean the people. Every year, a few members move away. Some have been with us for decades; some for just a year or two. Every year, new members begin to attend. Some are new to the neighborhood; some have lived here their whole lives. New parishioners are born, and some young or old pass away. Sometimes out of the blue it strikes me how much the church has changed, even just in the last four years, but it’s not a “directional” change. In other words, I don’t mean that we’re growing or shrinking, becoming younger or older; I simply mean that the collection of people who make up our church is constantly in flux, even as the church itself remains.

That’s probably true of our whole lives, as well. Each one of us is constantly rebuilt. Friendships come, and friendships go. We move on to new jobs, or trade one volunteering role for another. We move from place to place, or home to home. We may even change our minds, on rare occasions! And yet we are the same, even though by a thousand small steps we’ve traveled great distances from the way our lives once were.

But here’s the thing: even as we change, we remain the same. Whatever circumstances shape us, whatever situations in which we find ourselves, whichever ropes and planks we may replace, we are who we are. And “who we are” is nothing but the beloved children of God. Whatever choices you make, whatever you have done or left undone, wherever your voyage through this life takes you, however much you seem to have changed over the years, you are who you were at the moment you were baptized, when God looked at you, as God looked at Jesus, and said: This is my child, my beloved, in whom I am well pleased.