A Reading from the Acts of the Apostles.

Then after completing their mission Barnabas and Saul returned to Jerusalem and brought with them John, whose other name was Mark. Now in the church at Antioch there were prophets and teachers: Barnabas, Simeon who was called Niger, Lucius of Cyrene, Manaen a member of the court of Herod the ruler, and Saul. While they were worshiping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” Then after fasting and praying they laid their hands on them and sent them off. (Acts 12:25-13:3)

Here ends the Reading.

I laughed out loud while reading Morning Prayer on Tuesday morning, as I sat in bed with a cup of coffee. Tuesday was the Feast of Saint Mark the Evangelist, a great and prominent saint: the author of one of the four Gospels; the patron saint of the Egyptian Christian heartland of Alexandria and of the great city of Venice, home of the Basilica di San Marco itself; a man whose name graces five Episcopal churches in this diocese alone. And this was the sum total of the text mentioning Mark in the New Testament reading appointed for the morning: “Barnabas and Saul returned to Jerusalem and brought with them John, whose other name was Mark.” (Acts 12:25) The rest of the story barely mentions him; when the Holy Spirit speaks to congregations gathered in Jerusalem, it is to say, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul.” Poor Mark is left behind.

It’s not that this reading was chosen poorly for a day meant to celebrate St Mark. In the New Testament, the figure of “Mark” or “John Mark” barely appears. He’s mentioned in passing on occasion in the Acts of the Apostles or in the letters of Paul. Mark (the same Mark? another one?) also appears in the First Letter of Peter, where Peter calls him “my son Mark.” But these men named Mark never speak a word. They undertake no heroic acts. They’re not commended for their great faith. They’re listed in passing, and otherwise passed by. Even the Gospel of Mark itself doesn’t contain the name “Mark.” Its text identifies no author; while ancient manuscripts circulated with the title, “According to Mark,” the evangelist does not reveal himself to us at all. Where Paul would begin a letter, by identifying himself (“Paul, a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God…” [Romans 1:1]), Mark simply dives right in: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” (Mark 1:1)

Like so many of the titans of the early Church, the details of Mark’s story are simply not known. This mysterious evangelist, who’s believed to be the first to write a Gospel, the first to record in written form the details of Jesus’ life so that they would be made known to future generations, leaves us knowing next to nothing about himself.

And I think he might have liked it best that way.

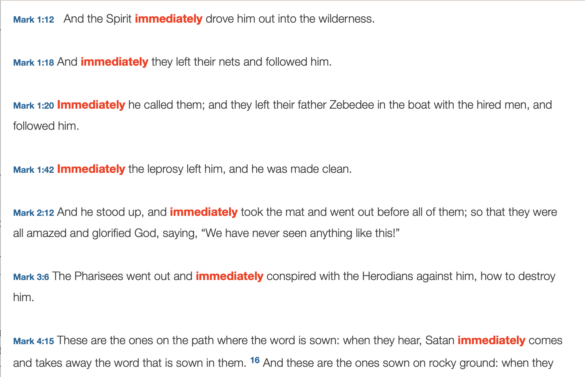

In my seminary New Testament class, on our final exam, we were given a few random verses from different books of the New Testament, and asked to identify or guess the book from which they came and explain our reasoning. So our study group collected, for each author, a few little “tells.” Mark was easiest: he writes with a plainness and immediacy that’s remarkable to see. (In fact, the adverb “immediately” appears 27 times in Mark’s short text; four times in the first chapter alone!)

Mark writes with focus, attention, and energy. His prose is not polished; there are very few frills. He is focused on, fascinated by, the person of Jesus and the story of this one year in his life. He can hardly spare a letter for description or context or a nicely-phrased way to set the scene: It’s all “Jesus did this, then immediately Jesus did that, then immediately Jesus did another thing.” You can hardly imagine Mark saying a word about himself, of all people, when there’s someone else’s much more interesting story to tell.

This might seem strange, in our era of artful author portraits and dust-jacket biographies, but to me, it seems like a relief. What matters, in the end, is not what Mark did or who he was. What matters is not his skill at building up the plot or the quality or polish of his prose. What matters is not the mistake he made when he was thirty years old, or his regrets about mistakes he’d made along the way. What mattered in the end, was the story he had to tell—a story so exciting and so strange he had to set it down immediately, his pen skipping along the page.

So here’s to you, Saint Mark, whoever you were. May we all be inspired to follow your example, sharing the good news of what God is doing in our world and in our lives. And may we all be comforted by the knowledge that, in a couple thousand years, whatever good or bad we’ve done, nobody but God will remember the details.