“A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey in. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solstitio brumali, ‘the very dead of winter.’”

— Lancelot Andrewes, Christmas Sermon, 1622

You may recognize, in these lines, the opening words of T.S. Eliot’s great poem “The Journey of the Magi,” (1927) which paraphrase Lancelot Andrewes’s Christmas sermon from three hundred years before. You may hear an echo of the great Christina Rosetti carol “In the Bleak Midwinter.” (1872) You may find yourself wondering—if you’re the type of skeptical and cosmopolitan person often found in the Episcopal Church—whether this isn’t all the result of an over-active English imagination. Surely—surely!—Jesus, having been born in the balmy Mediterranean, wasn’t really blanketed by “snow on snow, snow on snow,” as Rosetti would have us sing. Surely the Magi, traveling to Jerusalem from locations in Iran or Ethiopia or Arabia, wouldn’t have had “a cold coming.” Surely we’re simply projecting our own experiences of the cold, dark winter onto the days of Jesus’ birth, and surely this must be wrong.

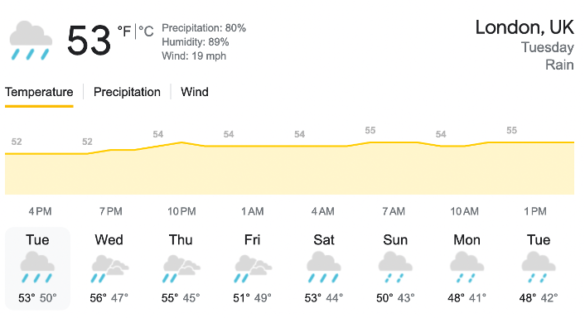

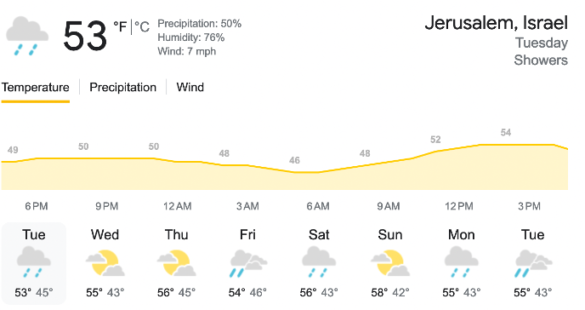

In reply to which I simply offer you today’s weather reports, from London and Jerusalem, respectively:

You see, the bleakness of the winter into which Jesus is born is not the bitter cold of an icy day in Boston, with clear skies but a biting wind off the Harbor. It is not the exertion of digging your car out from under a foot of snow, or slip-sliding your way down narrow sidewalks on your way to work. It is the unrelenting dreariness of a season too wet and cold to spend any time outside, and too warm to make a snowball. It is a world turned into mud by a month of cold rain, as the camels slip and slide their way through the hills, and you pray that the lid on your jar of frankincense is tight, because that stuff is ruined if it gets wet. And if you don’t believe Bishop Andrewes that this is “the worst time of the year to take a journey,” then—here I write on Tuesday, but the forecast looks the same all week—go outside for a thirty-minute walk in the forty-something-degree rain, and then come back and read this paragraph again.

It’s easy to imagine God as the God of our great celebrations, of Christmas joy and Easter triumph. And it’s comforting to be reminded of God as the God who is with us in our greatest tragedies, the Good Friday God of funerals and hospital beds. But we sometimes forget that God is just as much the God of dreariness, of cold, wet journeys through all the mud of life, of seasons in which we don’t have much to complain about but, don’t have much to rejoice about either. But this is the God of the Epiphany: the God who appears in the dark December skies to lead us with a bright star, the God whose warmth we feel at the end of a long day in the midst of a longer journey, the God of a thousand small epiphanies when days are short and weather sharp.