Sermon — June 27, 2021

The Rev. Greg Johnston

So I spent last week, as you may know, with my family in southern Maine. On Sunday morning, I did something I don’t usually do when I’m on vacation. I got up early and went to church. My mom had always wanted to visit this little outdoor chapel on the water down the road in Kennebunkport, and it was their reopening day for the season, so we decided to go. On our way there, my stepfather wondered if the Bushes would be there. He’d driven by their summer home on Walker’s Point the day before and seen the tell-tale signs of a presidential presence: security at the gate, a Secret Service boat in the harbor, and the American flag flying over the compound. And sure enough, as we roll into the driveway of the church we see two black SUVs. As we find seats, we note two fit men sitting in the second pew with little earpieces. Which means that the short grey hair and familiar ears in the first pew belong to none other than President George W. Bush, right next to one of the two communion stations.

Now, remember that I’m a little out of practice with receiving communion. And due to some combination of my clumsiness, and the light ocean breeze, and the fact that I’m a little flustered because I’m receiving communion standing not more than two feet from George W. Bush’s face—the priest places the wafer in my hands, and as I lift it to my mouth, it somehow flies out and lands in the grass at the former president’s feet, where, with my honed priestly reflexes, I immediately kneel down, grab the wafer, pop it into my mouth, cross myself, and walk away as the family laughs.

Of course, I’m laughing about it now too, but I immediately felt, as many people would, that hot and heart-racing feeling of shame. I can’t believe I just did that. It’s exactly the kind of thing that we feel when we violate one of our culture’s spoken or unspoken purity codes—in other words, when we accidentally let something holy brush up against something dirty. In my case, literally.

In her classic work Purity and Danger, the anthropologist Mary Douglas suggests that this is exactly the function of the purity codes that appear in cultures around the world: to separate things that are holy from things that are impure. We create definitions for who or what is “impure” and what is “holy,” for what counts as a sacred person or place and what can make it dirty; and then we create systems to keep these things apart. These don’t have to be particularly religious in nature. Imagine, for example, the average American’s response to someone who casually wipes his mustardy hot-dog hands on the American flag at a 4th of July parade. Visceral disgust, perhaps even anger. The flag is sacred; mustardy hands are dirty.

For us, of course, the “danger” of the title “Purity and Danger” is a little vague. After all, what do we think would actually happen if that dirty mustard touches the sacred flag? Lady Liberty won’t suddenly smite us for our disrespect. But in other times and places, it’s been clear. If unclean things were brought into the ancient gods’ holy places, people thought, they would become angry. At worst, they might strike back—or even flee. The prophet Ezekiel, for example, envisions priests performing impure sacrifices in the Temple in Jerusalem, (Ezekiel 8) defiling the holy place to such an extent that the Holy One himself is forced out. Unable to coexist with such impurity in the same place, almost magnetically repelled, God flees away in a fantastic chariot. (Ezekiel 10) And this is not some kind of bizarre prediction of the future. It’s Ezekiel’s explanation for the people’s current predicament of exile and suffering. The land became so impure that God was forced to leave, and left the people without a protector.

I said a few weeks ago that much of Mark is about struggles between Jesus and demons, but maybe I should have been more precise: Mark calls them “unclean spirits” just as often as he calls them “demons.” If you read carefully, the gospel takes on the tone of a struggle between “the Holy One of God” and “the Holy Spirit” and the “unclean spirits”—between the holy and the impure. While the words “impure” or “unclean” don’t appear in today’s gospel passage, people have often used this framework of holiness and impurity to try to understand what’s going on.

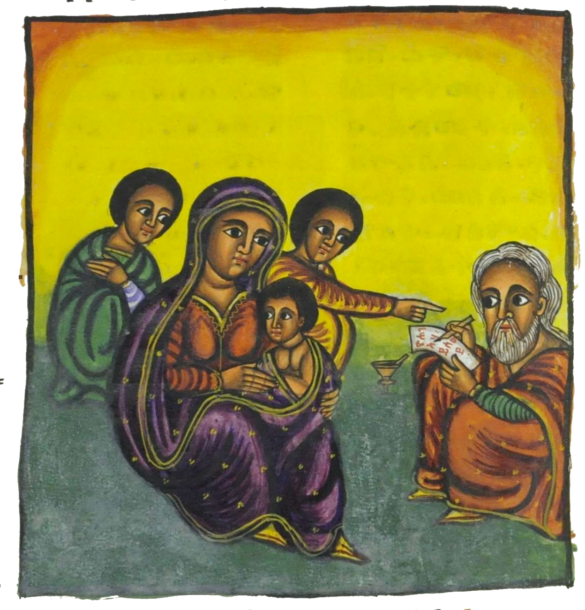

Both the unnamed woman in this story and the unnamed girl, after all, would have been in states of ritual impurity when they came into contact with Jesus. A woman experiencing this kind of irregular bleeding would be ritually impure in a manner laid down in Leviticus, as would anyone who touched her, and Leviticus describes the process for removing that impurity. (Lev. 15:19ff.) Likewise, touching a dead body conveys ritual impurity, and the book of Numbers explains how to cleanse yourself from that. (Numbers 19:11ff.)

Now there’s always a danger, at this point, of offering interpretations that can be anti-Jewish in tone, so it’s important to be careful. Impurity is not necessarily bad. There’s nothing wrong with being in a state of ritual impurity, any more than it’s wrong to get mustard on your hands while eating, as long as you don’t come into contact with what’s holy. The most ordinary cycles of life and the most extraordinary moments of birth and death all convey ritual impurity, and yet they are good, even divinely commanded. God tells the people to be fruitful and multiply, to care for the sick and the bury the dead. In village life, away from the holy place of the Temple, impurity was not such a big deal.

The woman’s problem, after all, is not that she’s cast out from society. It’s not that the doctors refuse to treat her because she’s impure. It’s that they’ve been all too willing to take her money without having a cure, and she’s suffered much and paid much to no avail! (Mark 5:26) Likewise, the young girl’s body isn’t avoided for fear of contamination. The room is so packed with mourners that Jesus sends them out to have some peace. (Mark 5:38) The problem is not that they’re in a state of impurity, but that they’re really suffering; perhaps this is why Mark doesn’t even use the word “impure” here.

Still, Mark has written a whole gospel about the struggle between “the Holy One of God” and “the unclean spirits,” (Mark 1:24) and now this holy one comes into the presence of two people who are, according to the culture within which they and Jesus live, unclean. There must be something here.

I think there is. Remember Ezekiel’s vision, in which the impure Temple drove out the holy God. Here, it’s the other way around. The Holy One comes into contact with that which is ritually unclean, and he is not driven out—he heals them. Now, we don’t live in a culture with this kind of purity code, so I hope you’ll excuse me making it a bit metaphorical. But we do live in a world in which we sometimes break one expectation or norm or another, in which our emotional responses of shame and anger and disgust are triggered, and Jesus remains. We worry and worry that we’re not good enough, that “what we have done and what we have left undone” has rendered us so imperfect as to drive God away. But the very opposite is true. God comes to us, amid all our “impurity,” amid all our brokenness and imperfection, amid all our unknown mistakes and all our known regrets. God comes to us, and there’s nothing we can do to drive her away. God is not disgusted with us or angry with us; God is here with us.

And more importantly still, God heals us. God really heals us. The power of the story is not that Jesus challenges purity codes; it’s that he changes people’s lives. He doesn’t just proclaim the woman cleansed; he stops the bleeding. He doesn’t just dismiss the idea that the girl’s body is impure as a silly superstition; he raises her to new life. God doesn’t just forgive us for our shame and our mistakes; God really heals our souls and our wills, making them holy, so that we may—one day!—live lives that more closely follow God’s holy way of love.

But—and here’s the catch—God does it on God’s own mysterious time. This story, you probably noticed, is a sandwich, with Jairus’s daughter as the bread and the woman as the filling. Jairus comes to Jesus with his daughter at the brink of death. (Mark 5:23) But Jesus doesn’t do what you would think. He doesn’t drop everything and come running. He begins to go with him, but then he stops and turns. “Who touched my cloak?” (5:30) And then he waits, and he listens. He listens to the woman long enough to hear “the whole truth,” (5:33) long enough to hear her twelve-year story of pain, for so long that by the time he’s finally headed on his way to the emergency sick visit—the girl is gone.

Is Jesus rude? Is he easily distracted? Is he trying to show off, intentionally upping the stakes of the miracle he’s about to perform? Maybe. But I think more than anything, this captures the paradoxical truth of Christian life: we believe that Jesus heals us, yet we suffer. We believe that Jesus saves us from death, and yet we die. We stand at the grave and proclaim the “sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life” even as “we commit” our loved one’s “body to the ground.” (BCP p. 501) No wonder they laughed at Jesus. (Mark 5:40)

But that’s what God chose to do in Christ: to turn things upside down. To take our intuition that holiness needs to live in great purity and dive into the midst of our messy lives instead. To take all the dropped communion wafers of our lives and turn them into the incarnate Body of Christ. To take our prayers for healing now and give us resurrection in the end, and to do it all on God’s own eternal time, while our souls wait “for the Lord,” as the Psalmist writes, “more than watchmen for the morning; more than watchmen for the morning.” (Psalm 130:5)