The Rev. Greg Johnston

What do we do when something we love is changing and disappearing?

This is the question that Elisha faces in the Old Testament story, as he’s reminded over and over that his relationship with his beloved teacher Elijah is about to end. It’s the question Peter and James and John can’t answer, when Jesus tells them he’s going to die and then takes them up on a mountain and appears transfigured, as they’ve never seen him before. It’s the question all of us face in our ordinary lives, as our marriages and children and jobs change and transition; it’s what all of us face in this extraordinary time, as we mourn the simple pleasures we’ve lost over the last year.

What do we do when the things we love disappear? Do we chase after them? Try to hold onto them? Freeze in fear? Or could there possibly be a different and maybe-better way?

I want to start with today’s gospel reading. To understand what’s going on, it will help to turn the Bible back a few pages. We’ve spent most of the last few weeks reading stories from the very beginning of the Gospel of Mark, and now we’ve leapt ahead in time, because on this last Sunday before Lent we always read the story of the Transfiguration. The story comes at the halfway point in Jesus’ ministry and in the Gospel. Jesus is done wandering around Galilee, healing people and teaching. Just as we begin our journey through Lent toward Holy Week, Jesus is beginning his own journey to Jerusalem, toward his trial and death. He’s just told his disciples that he must suffer, and be rejected, and die and rise again—and he’s told them that those who want to follow him will need to take up their own crosses, as well. The disciples are in denial, and try to argue with him, but Jesus is having none of it. He knows where he’s headed.

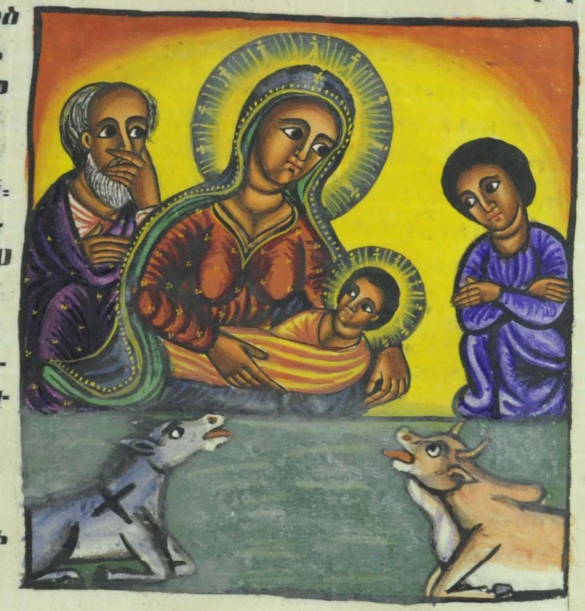

But for now, he takes his closest friends, and brings them up onto the mountain, and they discover who he really is. Moses and Elijah appear, the literal embodiments of all the Law and the Prophets—what we’d now call “the Old Testament.” The whole Bible, the whole Law and all the Prophets, point toward this man, at this moment. And the dazzling light of the glory of God shines through Jesus, who stands before them in “raiment…shining, exceeding white as snow; so as no fuller on earth can white them.” (Mark 9:3 KJV) (I’m not sure what a fuller is, but I always liked that one in the King James Version.)

And the disciples are “terrified.” (Mark 9:6)

And Peter, seemingly at a loss for words, suggests that they should build three little tents.

It’s clear from the story that Peter’s suggestion is wrong, although Jesus doesn’t say so, explicitly. For millennia people have argued about exactly why. Is it that Peter equates the divine Son of God with these two human prophets, and honors them equally? Is it that he tries to build God a physical home, when God wants to dwell within us? Is it that his suggestion is completely inadequate when faced with such an astounding display—that the glory of the Lord appears to him in all its splendor and all he can think to say is, “Okay! Okay! We’ll… we’ll pitch you a tent!”

Peter, of course, is baffled. “He did not know what to say, for they were terrified.” (Mark 9:6) He was terrified, I think, not only of this sudden transformation from a human teacher into something unbelievably more; but terrified, as well, by Jesus’ prediction of his own death. His closest friend and teacher is disappearing before his very eyes, and even in the few days he has left with them, he’s been transformed beyond recognition.

So what does Peter do? He tries to keep him in place.

It’s not so much that Peter wants to keep Jesus confined up on the mountaintop. The thing he wants to build him isn’t a temple, but a tent; he uses the same word he would have used for the Tabernacle, the portable tent-shrine that the Israelites long before had carried around with them on their wilderness wanderings. He knows that Elijah had ascended into heaven before his death, and perhaps he’d heard echoes of the same tradition about Moses; now he sees them descend to earth, and worries that they’re going to take Jesus back with them! So perhaps, he thinks, he can put it off a while. If only he can build a tent that’s nice enough, perhaps they’ll stay with him, forever! And this miraculous ministry he’s witnessed, this amazing time he’s spent with Jesus on earth, will never have to change.

But he’s rambling, afraid; he doesn’t know what to say, and this is all he’s got.

The prophet Elisha starts out with a similar attitude. This story is a typical Biblical combination of loyalty and comedy. Elijah knows his time on earth is drawing to a close; Elisha, his student and closest companion, is in denial. Three times Elijah tells him, “Stay here; for the Lord has sent me” to the next town over. (2 Kgs 2:1, 4, 6) Three times Elisha swears by God and by Elijah that “I will not leave you.” (2 Kgs 2:2, 4, 6) In Bethel, the prophets see Elijah pass and ask him, “Do you know that God is taking him away?” “I know!” he says, “Be quiet.” (2:3) And then again at Jericho, “Do you know that today God is taking him away?” “I! Know! Be! Quiet!” (2:5)

Peter and Elijah are in slightly different kinds of denial, but to more or less the same effect. Peter, who had rebuked Jesus when Jesus told the disciples that he would have to suffer and die (Mark 8:32) now tries to find some way to hang onto him. Elisha, who knows that Elijah’s going to disappear, still tries to stop anyone else from talking about it, and follows him to the very end.

But here, the two stories diverge, and I think we can learn something from what Elisha does. They’ve finally reached the Jordan, and Elijah has performed one final miracle, and he turns and asks Elisha, “What can I do for you, before I’m taken away?” And Elisha, wise despite all his denial, asks exactly the right thing: “Please, let me inherit a double share of your spirit.” (2 Kgs 2:9)

“Most of us in the West today,” writes the therapist and marriage counselor Esther Perel, “will have two or three marriages or committed relationships in our lifetime. [Those] daring enough to try…may find themselves having all of them with the same person.” Even those of us, in other words, who marry one person and stay married to them our whole lives, have more than one marriage. Perhaps there’s the first marriage, of romance and adventure; the second marriage, of child-raising or home-making and the long, slow trajectories of careers and family life; the third marriage, of retirement and travel; the fourth marriage, of sickness and death, of mourning and remembrance. Some people get divorced and remarried between those marriages; some have them all with one.

The same thing’s true of all our relationships. You can raise ten different children but only really have two; you can have five or six friendships with the same one close friend; you can work two or three different jobs over time without ever leaving your desk. And we all know you can be a member of three or four different churches, sometimes in the same parish and sometimes not.

We have all left behind old versions of our lives this past year. Our work has looked different than it did; our relationships with our spouses or kids or grandkids have been different from what we’d imagined; our retirements and travel and volunteering have been wildly different than we’d planned. And it’s natural to grieve those things, and want the ones that we’ve lost to come back.

But I alsp think that as we go through these transitions, Elisha’s insight can be helpful. His final prayer before Elijah disappears, you’ll remember, was not “Don’t go! Stay with me forever!” It was, “Let me inherit a double share of your spirit.”

As the last versions of our lives disappear from our sight, we face a choice. Do we deny that anything’s going to change until the very last moment, following it from town to town until the bitter end? Do we try to keep it with us, building a shrine to it up on the mountain?

Or do we pray to inherit a double share of its spirit; do we try, in other words, to carry the best of the stage that’s passing away into the new one that’s being born? Do we try to take what we have learned and how we’ve grown in the past, and bring them with us into the future?

As we begin to emerge from hibernation this year, that’s my prayer. Not that we return to the way things were. But that we rebuild our lives with the double-spirit of the best parts of the past: that we take up the mantle of the things that gave us life in 2019, and rejoice to wear them again; that we lay down the things that brought us down, and give ourselves permission to let them go; that we may “behold by faith the light of [Christ’s] countenance” in the last version of our lives as it passes away, and “be changed into his likeness from glory to glory” as we are reborn into new versions of ourselves.