Sermon — December 29, 2024

The Rev. Greg Johnston

So even though I’m a dad, I try not to repeat myself too often, although my cornier jokes do sometimes emerge again and again. But if you’ve known me for a couple of years, there are two things about my life that you may have heard me say more than once (or maybe not!) One is that I’ve lived my entire life within about a seven-mile radius of this point, except for the three years when I moved down south for seminary in New Haven, Connecticut. (Sorry… That’s one of the corny jokes.) The other thing that you may have heard me say many times is that I loathe—I despise—I simply cannot stand—winter in New England.

You might see this as a bit of a paradox: If you hate the winter so much, you might reasonably ask, why have you never moved? And, well… honestly, I don’t know. I think I just love the spring and the summer and the fall so much that I forget about winter, but then, inevitably, we arrive on some morning where the weather forecast tells me it feels like -3 outside, and it does, and I feel—inexplicably—both surprised and betrayed. And also very cold.

But these days, I’m lucky. I only have to deal with the shoulder-hunching, skin-drying, cough-inducing of the cold winter air and the dry winter heat; but I have an office with windows, and short walk to work. It’s the darkness that’s the worst part of winter, in a way, and for me, the darkness was never quite so bad as the year I spent commuting an hour on the subway to work in a windowless room. If you live in Boston and you spend the hours from 8am to 6pm with no windows, there will be a few months where you really just don’t see the sun.

And I actually used to count down: I’d think, on November 21st, okay, it will only be this dark until January 21st—we still have a month to go until the solstice, so it will be two months until we’re back to this depressing length of day. And I took great comfort in that. Because as the winter solstice approached and the days grew shorter and shorter, that time grew shorter, too, until I’d reach a day when I could say; This is the darkest day of the year. This is as bad as it gets. And every day to follow will be brighter.

Of course, this is only a trick. December 29 is still quite dark. The day is really short. There is still less light than there was back on December 1. But it feels much better to me, because by December 29, we’ve passed through so much darkness, and we’re headed in the right direction again.

“In the beginning was the Word,” St. John writes in the beautiful and famous prologue to his Gospel, “and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.” (John 1:1-5)

In the beginning was the Word, the capital-W Word, in Greek the Logos, the transcendent principle and underlying logic of the universe, through which all things were made and according to which all things operate. The Logos, the Word, is that indefinable, almost indescribable thing that artists and musicians call Beauty, that mathematicians and computer scientists call Elegance, that philosophers might identify as Truth—although any philosopher worth her salt would probably dispute everything I’ve just said. It’s what ordinary folks like us might be Joy or Love or Awe—that beautiful Thing that exists outside all things yet fills the best of things and suffuses them with goodness. The remarkable thing about the Prologue to the Gospel of John is not John’s claim that such a thing exists; that there is some divine order or structure to the universe. The remarkable thing about the Gospel is what John tells us in verse fourteen: the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. (John 1:14) Not that the Word became human, not that it walked the face of the earth, not that it was embodied, but that it became flesh, that messiest and most limited way of describing ourselves. That the Word of God took on frail flesh and lived a frail human life, coming in the world at a time of great darkness, and bringing new light. And “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

You know how this story ends. You know what’s on our calendar for the spring. You know the story from Christmas to Good Friday, and from Good Friday to Easter. If Jesus is the light of the world, and if “darkness” is John’s way of talking about the evil and the suffering of the world, then it makes sense to us as Christians to say that “the darkness did not overcome it,” because while Jesus died, he rose again, and he lives, still—and so we can understand why you might say “the light shines in the darkness,” in the present tense, “and the darkness did not overcome it,” in the past.

But the darkness isn’t only in the past. The light shines, even now, and that’s good news—but the light shines in the darkness, which is still here.

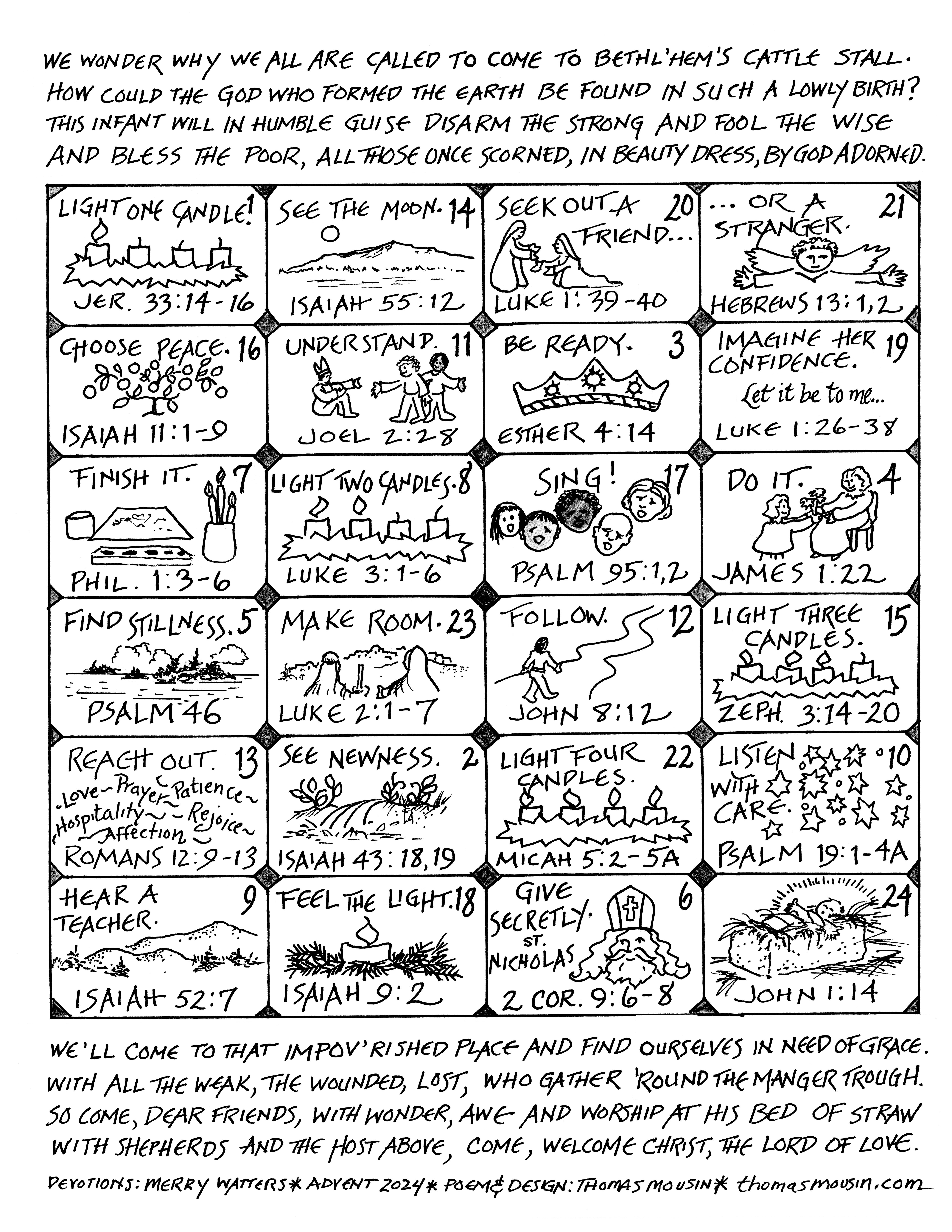

The world is still full of suffering and pain, injustice and oppression. The light has continued to grow. We’ve spread that single candle’s flame. Whatever its flaws may be, 21st-century America is a much better place than 1st-century Rome; in a thousand ways, from food security to medical treatments to the almost-global abolition of slavery, the world is less dark than it was two thousand years ago. And yet it’s still a far cry from an afternoon in June.

We live on December 29—not just today, but always. We live in a world in which the days are still dark, but the light has begun to grow. God has promised brighter days ahead. God “will not rest,” as Isaiah says, “until [our] vindication shines out like the dawn, and [our] salvation like a burning torch.” (Isaiah 62:1) The light will continue grow, and the days will become less dark.

You can’t always see this trajectory day by day. To stretch the analogy just up to the breaking point, the light we see isn’t only astronomical, it’s meteorological, as well. To put it in simpler terms, a rainy day in spring can feel darker than a sunny day in late December. But the clouds come and go, and the light continues to grow. As Dr. King said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Over the course of a human life, or over the course of human history, we make many wrong turns. We go down paths that turn out to be dead ends. Sometimes we can’t even see the light at the end of the tunnel.

But even now, while it’s still dark, we are not alone. “God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts,” Paul writes, freeing us from the power of evil, and making us children of God. (Gal. 4:6) “We have his glory,” and we have seen his light. Human history since the birth of Christ looks a lot to me like the darkness in church on Christmas Eve, as what begins with a single light shining the darkness spreads and spreads. We can keep one another’s candles lit. We can shelter one another against the draft. In a thousand ways, big and small, we can share that light with the people we love, with the people around us, and with all the people of the world. And we can know that the Holy Spirit is with us, leading us toward the truth.

“For the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.”