Sermon — May 23, 2021

The Rev. Greg Johnston

Years ago, when he was governor, Deval Patrick went to a town hall meeting in Lynn. A man stood up, and introduced the group he was with, and said he was speaking on behalf of the community of Iraqi refugees living in the area. Ahlan wa-sahlan! Governor Patrick said. “Welcome! Hello!” And his staffer, and the host of the town meeting, and the Iraqi refugees all stared at him for a second, and then the man speaking smiled and said to him, Ahlan bik! “Hello to you.” Nobody in the room knew that Governor Patrick had spent the better part of a year wandering around the Arabic-speaking half of Sudan after his Peace Corps position was canceled. It’s remarkable the kind of connection it can make to speak even just a few words in a person’s native tongue. (Unless it’s French. Never try to speak French to the French.)

But of course, language can just as easily divides us from one another as unite us. I’ll never forget the moment when Alice and I stepped into a sandwich shop in a small town outside Venice, heavily jet-lagged and—in Alice’s case—about five months pregnant, to be confronted with a glass case of unidentifiable sandwiches and a long menu in Italian only. “Excuse me,” I said with my terrible guide-book Italian, “do you speak English?” An apologetic shrug. “Spagnolo? Francese?” No. Clearly not a tourist sandwich shop. Unable to order lunch and on the verge of awkwardly walking out, we were suddenly rescued by a local man who was home for the week visiting his brother from his current home twenty minutes away from ours in Connecticut, who graciously translated the whole menu.

For all my love of language, I have to admit that even if we speak the same language, words just as often fail to communicate what we mean as they succeed. Some of you have been or are married. Some of you have worked for a boss or as part of a team. All of you, I know, have lived in the United States. And so you have firsthand experience of how easily communication can break down. We try again and again to express ourselves honestly and clearly, and it’s only rarely that we really feel heard and understood. As misunderstandings and miscommunications pile up, it can come to seem that we’re not even speaking the same language.

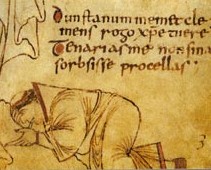

The Bible, of course, has a story to tell about why we can’t properly communicate with one another: “The Tower of Babel.” (Genesis 11) It’s been a few dozen generations since Noah and his family have emerged from the ark, and their descendants are still one big happy family. They have, the Bible says, “one language and the same words.” (Gen. 11:1) And they decide to build themselves a city, with a tower that stretches all the way up to heaven; so that, presumably, they might make themselves like gods. Like the gods in any ancient story about human pride, God undermines their project, “confus[ing] their language…so that they will not understand one another’s speech.” (Gen. 11:7) The one language of this one family splinters into the many languages of many peoples and, unable to communicate, they give up on their project and spread out throughout the world, leaving heaven safe from competition. God stops trying to work with all of humanity at once and chooses one people, the family of Abraham, through whom God will act in the world.

So it’s appropriate that on Pentecost, at the very moment when God’s kingdom begins to expand from the people of Israel to all the nations of the world, that God undoes the curse of Babel, at least for a moment. The two stories are mirror images. Humanity united tried to build itself a tower up to God, so God scattered them throughout the world and mixed up their languages. Now God is going to gather the people who have been scattered and to reunite them into one people of God, so God comes down among them and gives them the ability to speak to and understand one another again.

This is the miracle of Pentecost. The wind and the fire are impressive. But the point is the gift of language: the gift given to the disciples, on the one hand, to “speak in other languages,” (Acts 2:4) and to the crowd, on the other, to “hear, each of us, in our own native language,” (Acts 2:7) what the disciples are saying.

Some might want to “demythologize” these stories, seeing them as myths told to explain something about the way the world is. So Babel is just a story told to explain why people speak different languages. Pentecost is just a story told to explain how the gospel spreads from the small band of Jewish disciples in Jerusalem to Jews and Gentiles throughout the known world. But even if Pentecost were made up to explain the power of the early Christian message, it would be impressive. We’re talking about the message spreading to “Parthians, Medes, Elamites,” (over in Iran), “residents of Mesopotamia,” (that’s Iraq) “Cappadocia, Pontus, and Asia…Phyrgia and Pamphylia” (now all in Turkey), Egypt and Libya, Crete and Arabia, and even to the imperial city of Rome. And all within a few short years.

I like to believe this story of Pentecost. Maybe you have doubts. But without a doubt, the Holy Spirit’s power to help us speak is not a myth. It’s a gift. And it’s a gift we need, badly.

It starts with prayer. Our imperfect ability to speak and to understand applies to our relationship with God as much as our relationships with one another. It’s hard to pray! Those of us who are Episcopalians, used to the formal cadences of our liturgy, sometimes find it intimidating to pray in our own words. Even if that’s not the case, we sometimes just don’t know how to put our prayers into words, or even what we need to pray for. “We do not know how to pray as we ought,” Paul writes. (Romans 8:26) “But,” he continues, “that very Spirit intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words.” (8:26) It’s the wisdom of the title of Anne Lamott’s wonderful little book Help, Thanks, Wow: The Three Essential Prayers. We do not need to have the words to pray, we do not even need to know exactly what we’re praying for, we only need to want to pray and the Holy Spirit will pray for us in words that are beyond human words, because while even our most beautiful prayers can’t come close to building that tower all the way up to heaven, the “God who searches our hearts” has come down among us to hear those prayers. (8:27)

And it doesn’t stop there. Because the story of Pentecost isn’t a story of private prayer. It’s a story of evangelism, of people publicly sharing the good news of the great deeds that God has done for them, of being given the power to express them in terms that other people can understand, and of being given the gift of hearing them in a way that makes sense.

What great deeds has God done for you? If you are here right now listening to this, I guarantee you have a story to tell. God must have done something in your life, the Holy Spirit must have moved somehow in your heart, for you to be here this morning, sitting on Zoom or inside with a mask on, instead of enjoying yet another amazing spring day. It’s been fifteen months. You’re not here out of habit any more.

And this is all evangelism is. We don’t tell people that they’re going to burn. We don’t try to convince them that what we believe is true. We speak, as best we can, “about God’s deeds of power,” (Acts 2:11) about the things that God has been and done for us, and we trust the Holy Spirit to translate them, to give us the power to speak in words that others can understand, and to give the power to hear them in a way that connects with their own lives.

In the end, all this is God’s work, and not ours. If you’re as much a language-lover as I, you might have noticed that the disciples’ role in this story is passive, and God’s is active, until they receive the Holy Spirit. The disciples were all together, and heard a sound, and saw a flame, and “were filled with the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:1-4)—and then “they began to speak.” (2:4) All we can do is put ourselves in the right place. All we can do is bring ourselves to church, online or in-person. All we can do is adopt the posture of prayer. All we can do is to share our stories of faith. And then we wait, and we pray, and the Holy Spirit speaks in us and through us in ways we’ll never understand and may never realize for years. Like many things, the miracle of Pentecost is “now and not yet.” The renewal of our ability to speak and to hear began two thousand years ago and is still incomplete. So for now, we wait for things to unfold. For as Jesus says, the story is still incomplete: “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth.” (John 16:12–13)

Well, “I still have many things to say to you,” but this sermon’s long enough—“you cannot bear them now.” For now, I simply pray for the Holy Spirit’s gift of tongue: for the promise to be fulfilled that we may hear another more clearly, and speak to one another more honestly; that our language may become the things that brings us together and not what drives us apart, so that “when the Spirit of truth comes,” she may guide us “into all the truth.” Amen.