“Civilization is spread more by singing than by anything else.”

—Woody Guthrie

Music is one of our most effective tools for rebuilding solidarity and common purpose.

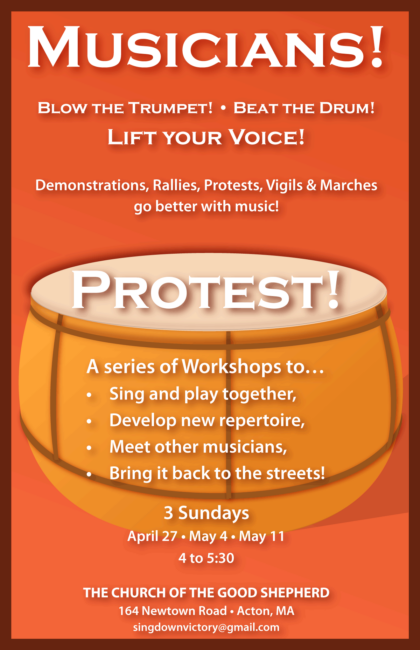

Join other musicians to write songs and renew old ones, build a repertory to take back to the streets to help renew the spirit of the people. Come with your voices and your instruments, and with your ideas. We build this music together.

In each workshop we will start by singing and playing together, then we’ll work on strategies to bring music to events, both large and small, get to know one another and begin to create a network of musicians who can call on one another to form ensembles and musical groups and share repertory. We will end, as we begin, with music.

The first workship will focus on protest music generally. In the second and third workshops we will look at introducing harmony, percussion and instruments. In all three workshops will will be working on ways to bring a richer musical presence to events, and at the same time developing ways to increase general participation.

We hope to build a network of musicians who want to bring music to the movement, to share strategies and techniques for protesting and acting to stop the destruction of our country and to build an online library of protest music — notated with lyrics and chords — in useful formats.

3 Sundays • April 27, May 4, May 11 • 4:00 to 5:30 pm

Church of the Good Shepherd

164 Newtown Road

Acton, Massachusetts 01720

For more information email SingDownVictory@gmail.com.

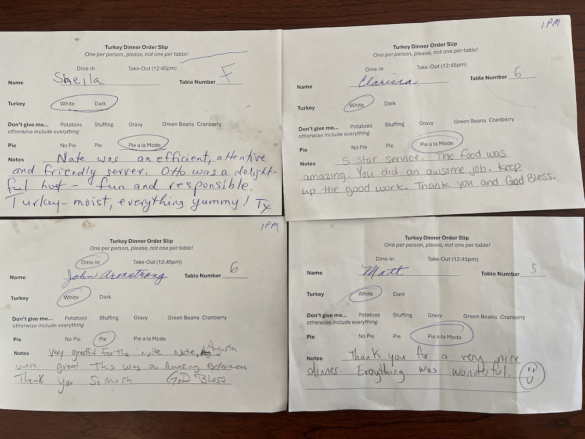

Notes on the first Workshop

- .We had six people at the first Workshop. The Workshop started with all of us singing, Pay Me My Money Down. I thought it was important to get started with music before we got lost in conversation. It seemed to work, as the ice was already broken before we talked! I was pleased that people immediately started filling in harmony — even before everybody knew the tune!

- After singing, we took chairs and went around the circle to introduce ourselves; and then talked for a while about what each of us hoped to get from these workshops and about how to create music at rallies and demonstrations, focusing on the acoustical difficulties of singing in the out of doors. Ellen talked a bit about the kind of song that worked best to sing with a crowd of people — Songs that a lot of people know are a good starting place, and call and response songs with simple, easily learned choruses will be an important resource. Several of us have already written alternative verses (which will be downloadable on this site).

- Portable amplifiers versus bullhorns? We concluded that bullhorns, while they could be effective in some circumstances, only amplified the voice in one direction; but there are battery operated, multidirectional, PA systems that can be carried in backpacks or in a case with a strap that goes over the shoulder. A quick search turned up a 100W example that sells for about $300.

- One of the particpants plays sax and is interested in forming a band focussed on the Resistance in the Fitchburg area. Keep your ears open for people who might be interested. Some suggestions were made on ways to make use of social media to find others in his area who might like to join.