During my first few months at St. Johns, I heard one phrase over and over again: “Getting Sundays right.” I heard it from members of the Search Committee as they interviewed me, from Wardens and Vestry members as we planned from the year ahead, and from parishioners just walking in and out of Sunday morning services. “What we want,” people would say, “is to get Sundays right.”

Of course, we sometimes need to be reminded that we’re Christians seven days a week, not just on Sunday mornings, that we bring our Christian identity and the truths of our Christian faith with us on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday as we go about our daily work and live our lives at home; that we are Christian, as the hymn goes, “Seven whole days, not one in heaven.” And this is important to remember. But it’s also true that our Sunday morning time together uniquely prepares us for those other six and a half days.

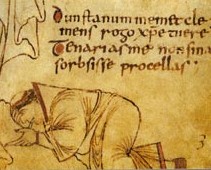

I was reading Morning Prayer this morning (Wednesday morning, as I write this), and it turns out that it’s the feast day of Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. I didn’t know anything about this 10th-century bishop. I’ll be honest, after reading his bio I haven’t picked up much. He was one of a number of monastic reformers who helped the Church recover from the shock of the Viking invasions, and brought back some of the splendor of its former days. What really struck me, though, is that he ended up with a really remarkably beautiful prayer in the book of saints Lesser Feasts & Fasts (2018), which is not always known for the beauty of its prayers.

I think it says everything about what we mean when we say we want to “get Sundays right”:

Direct your Church, O Lord, into the beauty of holiness, that, following the good example of your servant Dunstan, we may honor your Son Jesus Christ with our lips and in our lives; to the glory of his Name, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

“Direct your Church, O Lord, into the beauty of holiness, that we may honor your Son Jesus Christ with our lips and in our lives; to the glory of his Name.”

What a remarkable prayer. That’s exactly what it means to “get Sundays right.” We want to come here and be directed into the beauty of holiness—and then we want to go out and continue to honor Christ with our lips and in our lives, with the things that we say to one another and to the world and the things that we do for one another and for the world.

What an outstanding statement about Sunday-morning worship. This almost deserves to be taken away from Dunstan (sorry, Dunstan) and brought into the Sunday-morning liturgy. You might say it before worship on Sunday: “Direct your Church, O Lord, into the beauty of holiness, that we may honor your Son Jesus Christ with our lips and in our lives; to the glory of his Name.”

As I write this, we’re awaiting updated guidance from our bishops, which is supposed to be coming later this week. (Maybe I’ve already summarized it in News & Notes by the time you’re reading this!) We’re expecting them to loosen restrictions on in-person worship significantly, in accordance with the CDC and the Commonwealth’s recent decisions. This is a victory! We have, in fact, through all our efforts and the success of our public-health efforts, really reduced the risk of gathering together to “worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness,” as Psalm 96 goes. They’re still working out the details of questions like how to return to singing together, how long to keep masks for, and so on, and I would continue to urge everyone to be patient as we remember that not all adults, let alone teens or children, have even had the six weeks since vaccine eligibility necessary to be fully vaccinated. And so we won’t be jumping back in 100% right away, but this is really good news.

So direct your Church, O Lord, into the beauty of holiness, that we may honor your Son Jesus Christ with our lips and in our lives; to the glory of his Name. Amen.