I have a confession to make: as an opinionated and pugnacious Protestant teenager, I occasionally made fun of Catholics for what I thought of as the superstitious and vaguely-polytheistic practice of praying to the saints. (Although I never did this to my Catholic friends’ faces.) Maybe this was the result of growing up in an overwhelmingly-Catholic town and being told, when I was in third grade, that I wasn’t a real Christian because I wasn’t going to CCD; maybe I was just obnoxious. But I was certainly skeptical of all those saints. Isn’t invoking a saint just putting another barrier between your prayers and God? Does St. Anthony really have nothing better to do than help you find your keys? Isn’t declaring someone “the patron saint of _______” and then asking their prayers pretty much the same as the old Greek and Roman “gods of _______”? Saints seemed very suspect.

I was, of course, almost completely wrong.

I was wrong, first of all, because “praying to” a saint is less like “praying to” God, and more like asking a friend for prayer. The lengthy prayer known as “The Litany of the Saints” shows the difference. It begins by addressing God: “Lord, have mercy upon us. Christ, have mercy upon us. Lord, have mercy upon us…” After a few more prayers, the litany of the saints itself begins:

“Holy Mary Mother of God, pray for us.

Saint Michael, pray for us.

Saint Gabriel, pray for us.

Saint Raphael, pray for us…”

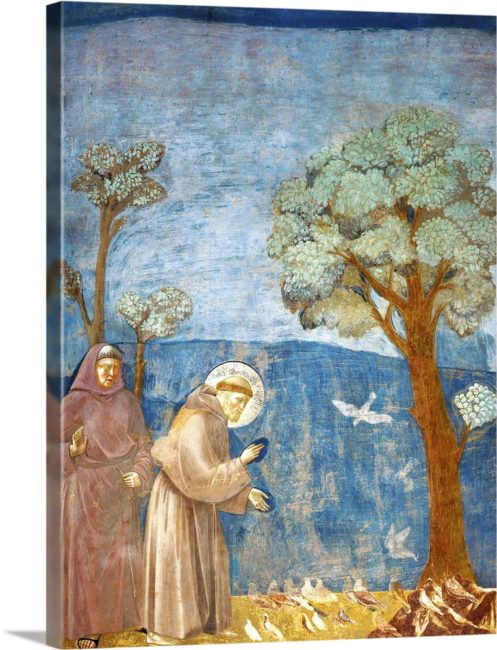

and on we go, through fifty-something saints, asking for the prayers of angels and archangels, apostles and evangelists, martyrs and bishops and holy people throughout the ages. Praying “to” a saint isn’t the same thing as praying to God at all; it’s asking the saint to pray with and for us, in the same way you might ask a pastor or a parent or a sibling or a friend for their prayers on your behalf. It’s a recognition and a remembrance that “to your faithful people, O Lord, life is changed, not ended,” and that the saints at rest in heaven can and do continue to pray with and for us, the saints still striving here on earth.

And it’s not just the famous and the influential saints, the ones we name in our litanies and after whom we name our parish churches, whose prayers we can receive. This is the most important contribution of our Episcopal tradition to discussions of the saints: the constant reminder that in the Bible, “the saints” are not a subcommittee of super-Christians, but the whole body of God’s holy people, of all those in any time or place who have been baptized into full membership in the Church. Some of the saints are not so saintly; some are very holy indeed. None are perfect. All are blessed and beloved members of the Body of Christ.

We need one another’s prayers. And we can ask for them, from any and all of the saints surrounding us: those whose faces we see and whose voices we hear in this world, and those who have passed before us to the next. It’s not a superstition. It’s not a barrier to God. It’s just the simple human act of leaning on a friend for prayer.

All ye holy ones of God, pray for us.